A NEW FRENCH STYLE : THE MIRACLE

SEASON 1, EPISODE 3 :

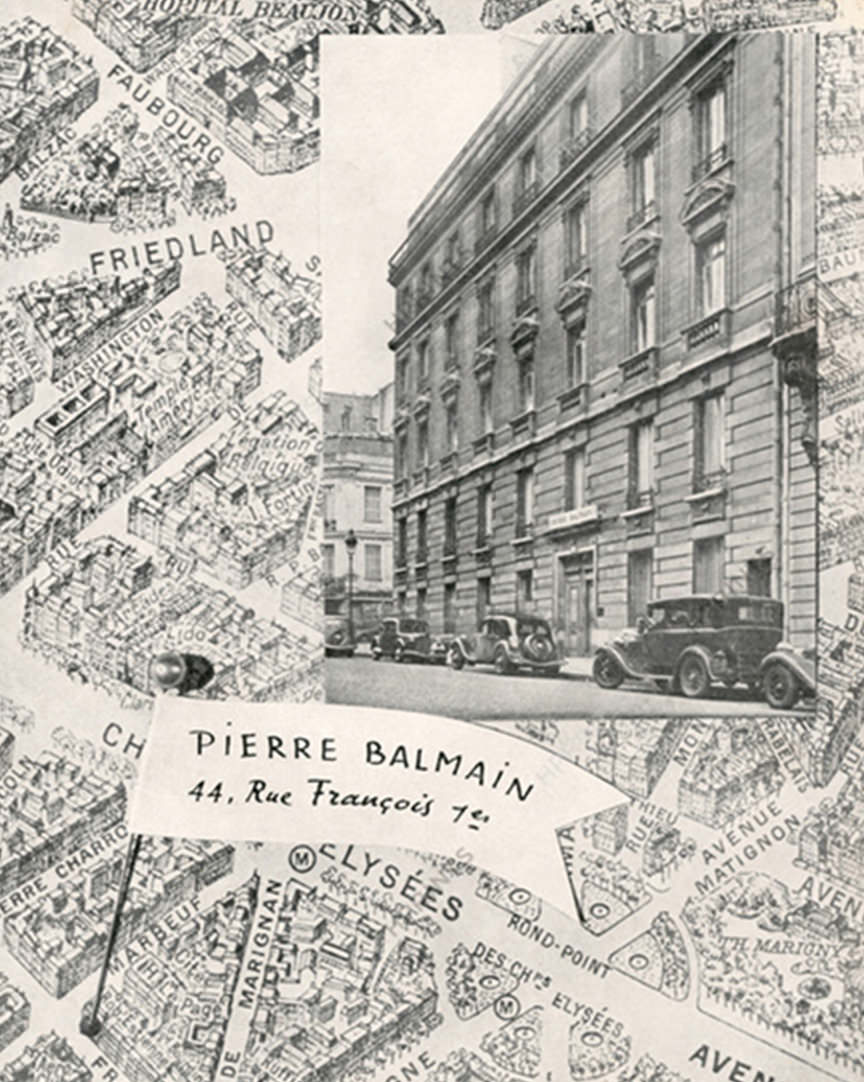

Pierre Balmain’s life changed radically on October 12th, 1945. That was the date that the young designer chose to schedule his new house’s first couture presentation to the public, held inside the salon of his new headquarters at 44, rue de François Premier, in the center of Paris’ famed “Golden Triangle” luxury neighborhood. Our third l’Atelier Balmain podcast explores the many challenges and struggles that the young Pierre Balmain faced as he worked on that first presentation—making very clear why the final, incredible triumph of that first collection is something that could be summed up as a “miracle”—a word that Pierre Balmain himself chose to describe that moment, in an interview with the French press, several years later.

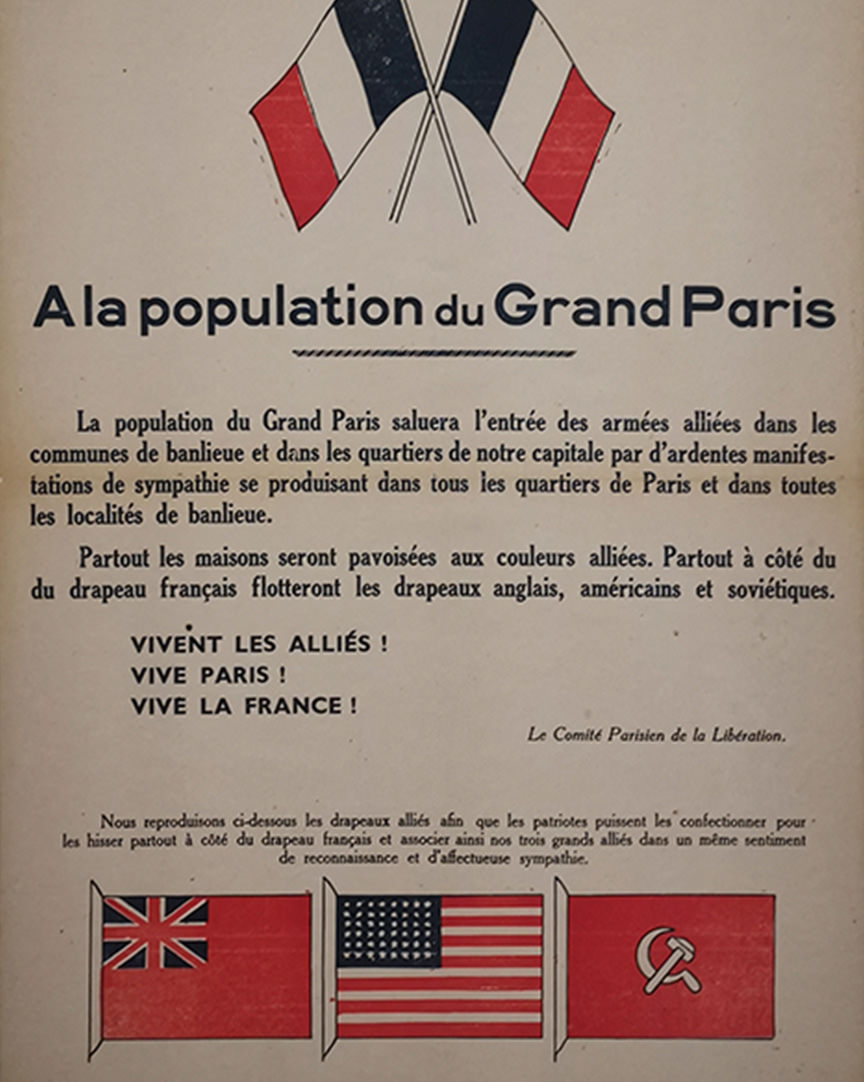

PARIS, LIBERATED

Pierre Balmain was only 30 years old in August 1944, when Paris was liberated. And once freedom arrived, Balmain decided it was time to found his own couture house, quickly setting up his atelier inside a recently vacated space on 44 Rue de François Premier—one which had been previously requisitioned by the Nazis during the long occupation. The designer’s memoirs make clear that he felt he simply could not wait any longer to make a change—and he definitely wasn’t the only Parisian looking for new beginnings at that time. All around him, one could spy brave green shoots, the first hopeful signs of the beginning of a cultural rebirth. France was entering into what would later be called its année zero — Year Zero. After so much had been destroyed, suddenly so much seemed ready to start anew. Startling and exceptional visions in music, literature, theatre and cinema were being pushed forward by the remarkable young talents of that time, creating an explosion of creativity that began in Paris immediately after the war and continued for decades afterwards.

FRENCH FASHION INDUSTRY STRUGGLES

Both the new French government and the Paris fashion houses were eager to promote their designers and the latest post-war collections, in order to help this important industry begin to recover. But, with the restrictions, shortages and lack of tourists, buyers and press—any sort of lavish presentation was simply out of the question. There was not enough fabric, money, heat, reliable electricity or workers. So, the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture—the powerful trade organization governing every element of French fashion—was forced to improvise. And it came up with a fantastic and original solution. Paris’ fashion leaders dreamt up an entirely new and enchanting way to present the type of creations that only Paris fashion is capable of designing,

THE THÉÂTRE DE LA MODE

In early March 1945, a special exhibit was set up inside the Louvre Museum. 60 Paris couturiers helped install what they called the Théâtre de la Mode. They relied on about 200 dolls, each one specially created from thick wires and plaster heads, and all of them set up on a series of 15 miniature stages that had been created by some of Paris’ most talented designers, including Jean Cocteau and Christian Berard.

Each participating couturier created about five outfits, giving each house’s dolls a selection of morning, afternoon, cocktail, dinner and evening looks.

Today, The Théâtre de la Mode forms a part of the Maryhill Museum, which generously gave us permission to use their photos to help tell this incredible story.

Each mini outfit in the Théâtre de la Mode was amazing — they were all perfectly scaled-down versions of couture designs, with working zippers, buttonholes, shoes and jeweled brooches executed in exact scale—every detail was perfectly cut, pleated and draped and everything was fitted exactly—just as you would expect from Paris’ best couture tailoring.

The dolls were given miniature hats created by Paris’ best milliners, as well as wigs created from human hair and created by the most famous hairstylists in Paris—Antoine and Guillaume. The doll-sized tiaras, bracelets and necklaces came only from the best names, including Cartier, Chaumet and Van Clef and Arpels.

1 / 3

The 200 designs were grouped by styles.

For the collections of daytime suits and dresses, the sets were inspired by many Parisian post-card scenes— the mannequins were posed window-shopping in the Place Vendome and strolling outside the Palais Royal. Most locations looked to everyday life from pre-war times, including sunbathing at Deauville’s beaches, or a night at the opera.

Admission was charged to raise money for the French war relief and the Louvre exhibit attracted nearly 100,000 visitors.

After Paris, the Théâtre de la Mode traveled to London, Stockholm, Copenhagen and Barcelona for the rest of 1945. Then, European tour finished, the mannequins returned to Paris to be outfitted with new clothes that the houses had designed for the 1946 season and then the exhibition traveled to the United States—so, those dolls’ dresses were among the first Balmains presented in the United States. This gray tulle Balmain dress, set on a witch flying from the rafters of a bombed-out maid's room received a lot of attention—as much for Balmain’s designs as for the setting, which was a surrealistic scene dreamed up by the famous Jean Cocteau.

Pierre Balmain designed this evening gown in gray tulle, embroidered in a scroll pattern with steel-gray and rust beads for the Théâtre de la Mode. The full skirt has layers of almond-green and gray tulle, with irregular hem. The gloves, in pale yellow suede, are designed by Faré.

44 RUE FRANÇOIS PREMIER

Before he could present his first collection, Pierre Balmain had some major obstacles to overcome. The empty real estate that he had stumbled across shortly after the Nazis had fled a newly liberated Paris, was definitely in the perfect location. 44 rue de François Premier is smack in the middle of the famous Golden Triangle — le Triangle D'or— which is an incredible area of real estate bordered by three of the French Capital’s most aristocratic Avenues — the Avenue Montaigne, known for its incredible boutiques, the stately Avenue Georges V which holds some of the city’s most important luxury hotels and, of course, the Avenue des Champs Elysées, which is known to the French as “La plus belle avenue du monde” (the most beautiful avenue in the world).

The building itself, like so many in that neighborhood, is a very handsome five-story Haussmannian structure. It follows all the rules of that quintessential Parisian architectural style. Before the war, it had been a beautiful residential building—up until the Nazis had requisitioned it during the occupation. After the liberation had forced the Nazis out, the landlord was determined to change all of his leases into commercial agreements—which allowed Pierre Balmain the rare opportunity of grabbing a showroom space in the very coveted neighborhood…

But even though the address and the façade were impressive, the new space wasn’t exactly suited to the needs of a designer—it was far too small of a space and it was still laid out for apartment living. Balmain was forced to convert the old bathroom into his design studio, creating a desk by laying a board across the bathtub. Fabrics were stored in new shelves thrown up quickly in the kitchen. The long hallway was given over to the switchboard, desks and racks of clothing.

Like every new designer, Balmain had to deal with money problems as he designed his collection. To save money he moved into the space—working and sleeping there at night, as he worked on his first offerings during the day. His early backers changed their mind at the last moment, forcing him to scramble and plead with bankers and search for new investors. Then, when 200,000 francs went missing from the office safe, his mother actually ended up prying the diamond off her engagement ring to pawn for needed funds.

And there were problems with the lease that he had signed. The landlords had signed over the space even though the new French government had passed a decree making it clear that all properties that had been requisitioned by the Nazis were to be handed over to De Gaulle’s new government. Post-war government plans called for the space to be converted into offices for the Economics Ministry. Balmain received many threatening letters and visits from gendarmes threatening to evict him.

THE MIRACLE

Pierre Balmain’s first designs could be summed up in two words: luxury and simplicity.

There’s a very long and slender spirit that’s easy to notice—even the pleated skirts managed to remain very slender. It’s all about softness and femininity—shoulders are natural, waists are cinched and there’s lots of skillful draping

To provide a bit of contrast to the collection’s slim pants and sheaths, for evening Balmain threw in some full-skirted styles, as well.

When it was over, as every designer does, all he could do was wait for the reviews—and they were amazing.

The collection itself was more than well received, with magazines like l'Epoque calling it “very smart and seductive,” Les Lettres Françaises praised “the collection’s fireworks of new ideas” Point du Vue praising the “Elegance, sobriety and pretty details” and Femina mentioning that ever since the day of the show “Everyone in Paris is asking: have you seen Balmain?” Minerve simply showed one of the hats from the collection, with a photo caption reading “Hats off to Balmain’s great elegance, strict tailoring and refined embroidery”

And the critics were also ready to pile praise upon the collection’s designer, Pierre Balmain, with Action magazine labeling him as the newest star in fashion’s constellation who was enjoying an instant success, L’Art Et Mode calling Balmain a magnificent artist who was breaking traditions and Gavroche declaring that this very Parisian collection meant that Pierre Balmain could now be considered to be among the top level of designers —a view echoed by The New York Herald Tribune, which stated that the successful new collection allowed the new house of Pierre Balmain to be considered on same level as that moment’s other great houses of Paris, including Balenciaga, Lelong, Molyneux, Patou.

FLEUR DE PARIS

A hit song from the era, Fleur de Paris— Parisian Flower, which plays throughout this episode— was written right after Paris’ liberation and it reflects the new optimism of the moment. The famous crooner Maurice Chevalier made this tune a hit, and its message was hard to miss, as he sang about the blue-white-and-red flower that Parisians had kept to themselves for four long years, locked up and hidden away, in the hopes that someday better days would come. Finally, the lyrics proclaimed, better days were returning, and it was time to celebrate a new dawn, new hopes and a new blooming of the beautiful fleur de Paris.

C'est une fleur de Paris,

Du vieux Paris qui sourit,

Car c'est la fleur du retour,

Du retour des beaux jours.

Pendant quatre ans dans nos coeurs

Elle a gardé ses couleurs,

Bleu, Blanc, Rouge,

Avec l'espoir elle a fleuri,

Fleur de Paris.

It’s a Parisian flower

From the old Paris that smiles

Because it is the flower of returning

The returning of good days

For four years, in our hearts

She has kept her colors:

Blue, white Red

Wit hope, she has now bloomed

The Parisian flower

Photo Credits:

01 : Théâtre de la Mode: “La Grotto Enchantée” (The Enchanted Grotto), original 1946 fashions and mannequins from set by André Beaurepaire (recreated by Anne Surgers); Collection of Maryhill Museum of Art- 02 : Théâtre de la Mode: Lucien Lelong, cap-sleeved turquoise and white chiffon dress with cowl-draped bodice. White organdy collar and cuffs. Matching chiffon sash wrapped and tied in a large bow.

Natural straw picture hat with ivory grosgrain ribbon: Legroux. Coiffure: Charbonnier - 03 : Théâtre de la Mode: photos of garments and hats in museum storage as they are waiting to be placed on the mannequins. Collection of Maryhill Museum of Art

- 04 : Théâtre de la Mode: “Palais Royale,” original 1946 fashions and mannequins from set by André Dignimont (recreated by Anne Surgers); Collection of Maryhill Museum of Art

- 05 :Théâtre de la Mode: “Le Jardin Marveilleux” (The Marvelous Garden), original 1946 fashions and mannequins from set by Jean-Denis Malclès (recreated by Anne Surgers); Collection of Maryhill Museum of Art

- 06 : Louis Touchagues chose to re-create the Rue de la Paix and the Place Vendôme, one of the most elegant of Parisian settings. Photo courtesy of Maryhill Museum of Art

- 07 : Lucien Lelong, short dance dress.

Short-sleeved candy-pink crepe top (synthetic) with draped fichu held by roses. Full skirt in black surah (synthetic) with fagotted hem. Coiffure: Charbonnier Black suede shoes piped in black leather: Elie Pink kid gloves with black suede bows: Faré Belt: Mabille Flowers: Judith Barbier Photo courtesy of Maryhill Museum of Art

- 08 : Paquin, long evening dress in purple satin (Colcombet).

Fitted bodice with shoulder straps. A wide swag of pink and violet satin drapes around the hips and falls over the big full skirt. Coiffure: Jean-Pierre Purple satin pumps: Richomme Long pink kid gloves: Faré Clip, hair ornament and bracelet in gold, platinum and rubies: Chaumet. Photo courtesy of Maryhill Museum of Art - 09 : Mendel “Rose de France”.

Full-length ermine cape lined in pale pink satin. Matching pink satin evening dress, the strapless bodice and full skirt embroidered in a scroll pattern of old-gold sequins. Coiffure: Desfossés Embroidery: Gaby Pale pink kid gloves: Hèrmes. Photo courtesy of Maryhill Museum of Art - 10 : Schiaparelli, long sleeved evening dress with pink satin fitted wrapover bodice and flared skirt made of wavy horizontal bands in shades of fuchsia, lilac, ad violet. Between each band, metallic embroidery covered with a zigzag of white thread.

Coiffure: Marc Ruyer Pink kid gloves: Faré Embroidery: Lesage Diamond, rupy and platinum tiara, epaulettes and belt: Van Cleef & Arpels. Photo courtesy of Maryhill Museum of Art - 11 : Worth, Ivory silk damask evening dress with large floral pattern.

Fitted bodice with wide straps, entirely embroidered in sequins and gold thread in a twig and stylized flower motif. Two long pointed side panels of the same embroidery fall over the full skirt. Coiffure: Gabriel Fau Photo courtesy of Maryhill Museum of Art

- 12 : Théâtre de la Mode: “Ma Femme est une Sorcière” (My Wife is a Witch), original 1946 fashions and mannequins from décor by Jean Cocteau (recreated by Anne Surgers); Gift of Gift of Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne and Paul Verdier, Collection of Maryhill Museum of Art

- 13 : Collection of Maryhill Museum of Art

Video Credit:

Balmain Presentation 1982Credits :

Balmain Creative Director: Olivier Rousteing- Special Podcast Guest: Lynn Yaeger

- Music: “Fleur de Paris” by Maurice Chevalier

- Additional Music: Jean-Michel Derain

- Episode Direction and Production: Seb Lascoux

- Balmain Historian: Julia Guillon

- Episode Coordination: Alya Nazaraly

- Research Assistance: Fatoumata Conte and Pénélope André

- Digital Coordination/Graphic Identity: Jeremy Mace

- Episode researched, written and presented by John Gilligan

To explore further:

Pierre Balmain’s Autobiography: My Years and Seasons, Doubleday, 1965