FUN, FEAR AND FATE

SEASON 1, EPISODE 7 :

BALMAIN'S DECORATED WAR HERO : GINETTE SPANIER

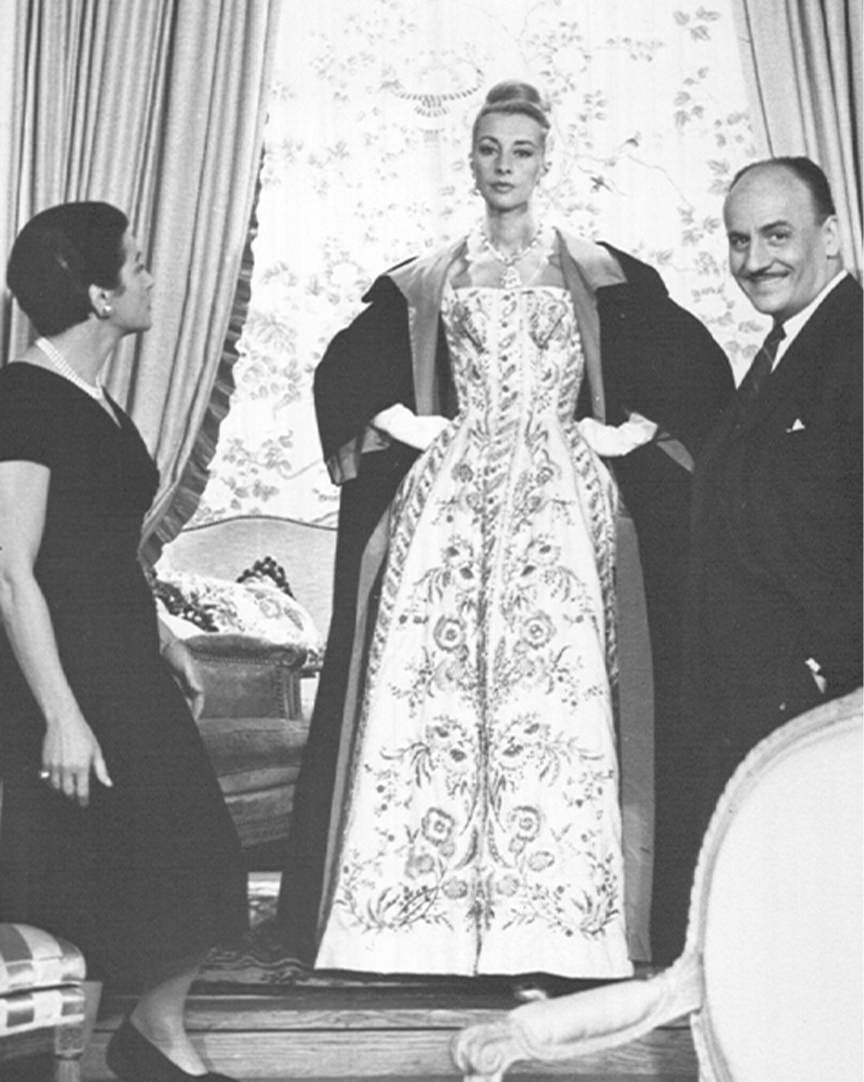

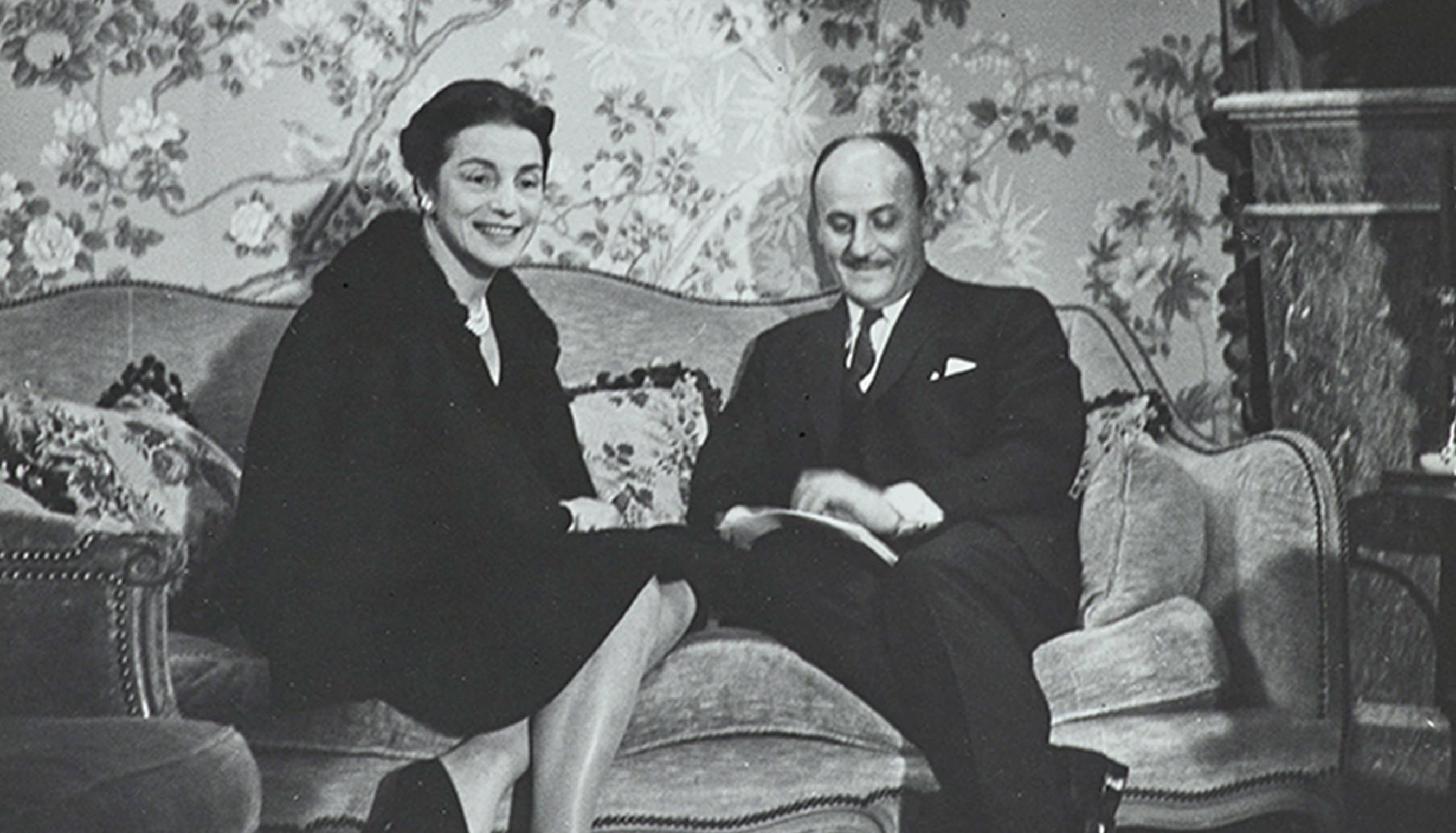

This episode of l’Atelier Balmain explains a bit about the functioning of mid-century Balmain by focusing on the life and work of one key member of the small team overseeing the rapid growth of house during this important era: Ginette Spanier.

Spanier was the house’s first Directrice—the first Director of Balmain—and she was a extremely savvy businesswoman, skillfully guiding Balmain’s retail strategy for almost thirty years. Spanier was also a minor celebrity—and not just because she formed close friendships with many of the world’s leading theatre, movie and music stars who relied on fashion guidance from her and Pierre Balmain. Spanier’s fame was also due to the success of her best-selling series of memoirs. Those autobiographies presented Spanier’s incredible life story. And her amazing life story, as was noted in the snippet from a 1972 broadcast of “This Is Your Life” that we use to begin today’s podcast, can be summed in three words: Ginette Spanier had a life of “fun, fear and fate.”

As Directrice of the house during its formative years, Ginette Spanier played a decisive role in helping shape Balmain’s post-war growth, practices and image. She worked very closely with Pierre Balmain and his design team, helping decide what would be shown in each season’s collections. She also oversaw the house’s retail team and worked closely to build relationships with the most important clients of the house. Her love of name-dropping is mind-blowing—but the friendships that she formed with many of the biggest celebrities of the time was of key importance for the house.

Her work in haute-couture luxury and her many close friendships with leading actors, writers and singers of the time definitely helped convert her three autobiographies into best-sellers... but, more than anything else, it is her amazing wartime bravery and heroism that truly make Ginette Spanier stand apart.

Spanier, a French-born Brit, and her French husband, Dr. Paul-Emile Seidmann, were both Jewish. For their own safety and survival, they were forced to flee Paris shortly after the Nazis began their occupation of the French capital. They then spent over four years on the run—being sheltered by brave résistants, farmers and rural villagers, as they traveled from region to region in search of a safe place to hide.

Somehow, they managed to survive. And once they finally reached a newly liberated Paris, they were determined to play a part in helping the allied forces finally end the war. Paul-Emile Seidmann began working with the new French provisional government, eventually overseeing rehabilitation programs for the deportees who had managed to survive and return from the death camps and slave-labor factories.

Spanier signed on with the American troops, assisting them in the recruitment of young students, building up a bilingual corps of trained secretaries, switchboard operators, assistants and translators, to help as the allies pushed further and further east, across France and, finally, into Germany.

And even after Berlin fell and the final victory was assured, Spanier was determined to continue to help the Allies—in order to ensure that the war criminals were brought to justice.

Ginette Spanier volunteered to work for the Nuremberg trials. Those historic trials, overseen by the victorious allies, prosecuted captured leaders of Nazi Germany for having planned and carried out the Holocaust, as well as other war crimes. Nuremburg was actually a series of military tribunals, lasting from November 1945 until October 1946. Spanier oversaw the creation and functioning of a bilingual support staff for the Allied prosecutors.

In recognition of her support of allied troops and her assistance in prosecuting some of the twentieth-century’s most horrific war criminals, Spanier was awarded the United States Medal of Freedom—which President Truman had established to honor those civilians whose actions aided in the war efforts of the United States and its allies.

In her interviews, lectures and writings, Spanier continually stressed that the many years that she spent both fleeing and prosecuting the Nazis had changed her forever. After she returned from to Paris, long past the end of the Nuremberg trials—even decades after she first began overseeing the daily operations of Balmain—she could not forget the essential lessons that she had learned during the war.

BALMAIN'S FIRST DIRECTRICE

In her first autobiography, “It Isn’t All Mink,” Ginette Spanier explained what that role of Balmain’s Directrice entailed:

“Basically I would say the directrice is responsible for every human problem throughout the part of the firm which the public can see. The workrooms are not her business. But it does become her business if a certain dress does not fit, so she has to co-operate with the fitters responsible for their workrooms. If the terrible shrieking of two mannequins coming to blows over who shall show what dress should penetrate to the ears of, say, the Begum Aga Khan, then that also is the fault of the directrice. If the tearing and snarling sounds made by two vendeuses quarreling over a customer should reach the customer, that is the directrice’s fault too. If a customer does not pay her bill, that somehow is also the directrice’s fault. And so on, and so forth, right round the clock”

It Isn’t All Mink

Collins 1959

V&A Publishing 2017

THE BALMAIN CABINE

In post-war Paris, each of the famous haute couture houses relied on a whole team of full-time in-house models. These were women who worked all day at the house, each linked to a specific series of designs each season, couture creations that had been specifically created for them and fitted to them. And these same house models would form part of the daily shows that the houses would put on for their clients, every morning and afternoon.

These models formed part of what was called the house’s “cabine”. Cabine is a French word — it literally means “cabin” — and refers to the backstage room where models change from one couture creation to the next. And that same word was used figuratively to refer to the distinct group of models employed at each couture house. Pierre Balmain, like most Paris couture designers, had his own specific Cabine — the Balmain Cabine. Each season, there were about 10-12 women working full time at the Balmain cabine.

And for Balmain—and for every couturier—it was important that all the women in his house’s cabine reflected the distinct look and spirit of the house. Each model in the cabine had a distinct role to play. Each was seen as someone with a distinct type of spirit and look. For example, some women would be hired because they had a young fresh look, which would be linked to more sporty and young designs. And other models might be seen as more sophisticated— and they would be the preferred mannequins for elegant evening couture designs.

The cabine models were very closely linked to the season’s collections. They would inspire Balmain’s beginning sketches and starting from that moment, they would then be tied to every step in the creation of a couture piece. The model’s name was written on a ribbon that was sewn into the dress and from one stage to the next, the creation would be tailored and styled to best fit and suit her, specifically.

So, the more a model inspired the designer, the higher the number of creations she would end up presenting during the couture shows.

And, when the cabine models weren’t involved in fittings, they were often taking part in daily shows for customers. At Balmain, there was a daily 3pm show. There were also more intimate presentations in the morning, usually around 10am, for those customers who asked to see just a few specific designs.

And backstage, life in the cabine, was tough—from what models and dressers have written, it sounds like it was way too hot and way too crowded. People could be anxious and worried—and tension and competition could sometimes be high…

To get an idea of what it was like back in those days, you can click the link below to see an amazing series of shots by the American photographer Mark Shaw, for Life Magazine, in 1954. He shot the Balmain cabine as the models changed for the shows. The women and the clothing are both, of course, beautiful — but you can clearly see that the space is very crowded and you can sense the anxiety and the frenzied atmosphere, as the women try to quickly change for their next turn in front of Balmain’s customers.

1 / 11

THE EARLY BALMAIN SHOWS

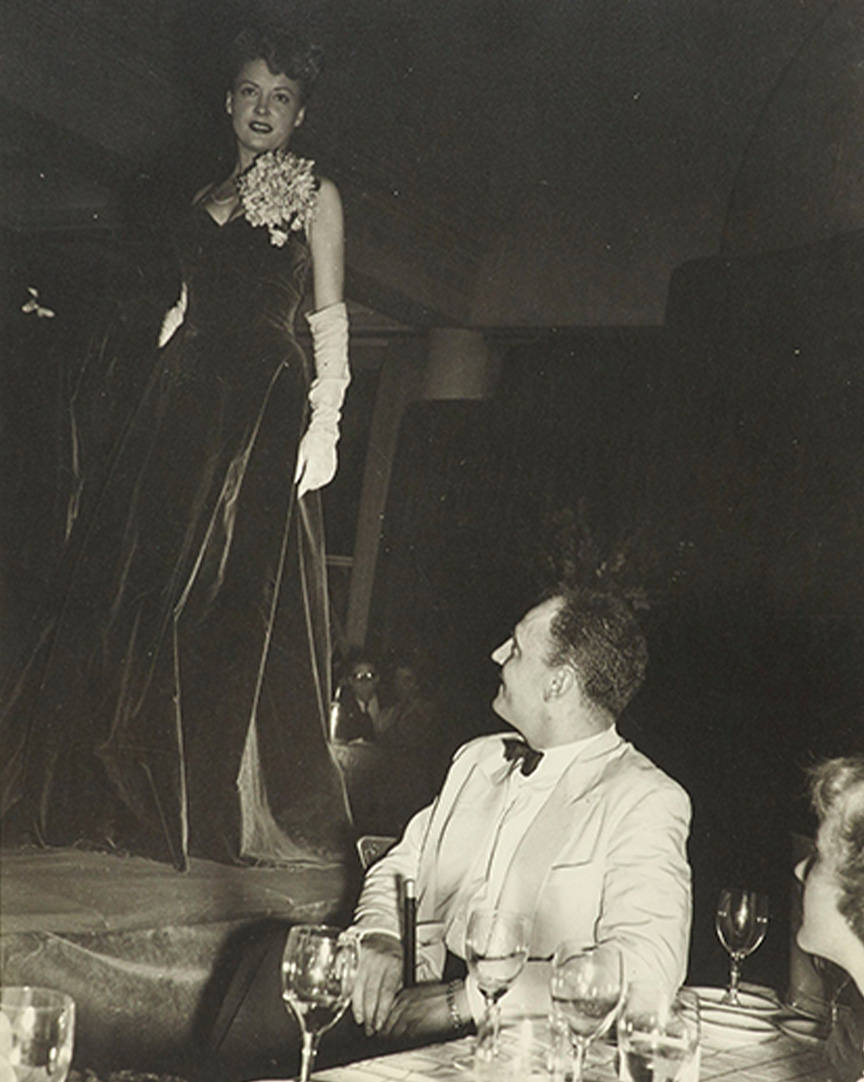

Immediately post-war, haute-couture fashion shows in Paris were light years away from what we are used to seeing today. During Pierre Balmain’s early years, his couture presentations were shown in the house’s salons, at 44, rue François Premier. Those presentation spaces were designed like aristocratic sitting rooms — with mirrors and paintings on the wall and the guests seated on small golden chairs or uncomfortable couches.

There were definitely no blaring runway soundtracks. Just a single model at a time, meandering slowly through the space—allowing the guests a chance to examine the piece closely, ask the model to twirl and sometimes even reach out to touch the fabric. Usually, the model carried a card with a number, indicating which design she was wearing. That same number — and perhaps a small description of the design itself— would also be announced on loudspeaker, usually by Ginette Spanier, in English and French.

And front-row seats were definitely not given over to influencers or reality stars. Those daily shows were not marketing events—it was all about sales. The goal was simply to present directly to buyers. Often, members of the house’s sales staff—les vendeuses—would be standing close to the most important clients, as they watched a show, whispering, to check and see if there was any interest, as each new design passed by. Once a client made clear which designs she liked, the vendeuse and shopper could go to a fitting room, to be shown the pieces individually by the house models. Any final purchases would then be created during a series of atelier couture fittings, a process that stretched out over six weeks or so.

PRALINE

Unlike most showroom models, Praline actually became a celebrity in post-war France.

She was born to a working-class family in 1921—her father was a bus driver and her mother worked in a glove factory—and her real name was Jeannine Marie Lucienne Sagny. Just like so many others before and after her, Praliine was eager to move to Paris and become a star. She originally worked as a shopgirl and then as a stenographer —but she was finally able to get a job as a house model at Lucien Lelong, where Balmain was designing alongside Christian Dior.

Balmain and Praline became very close, very quickly. She had an upbeat and fun personality, which Balmain compared to that of a “Paris Urchin”—but he also saw in her the “personification of feminine charm” and the “regal elegance of a great courtesan.” At Lelong, Balmain loved how she could immediately switch from one style to another… she could be all gamine in a beach outfit and then walk out into the showroom a few minutes later as an elegant aristocrat, in a long gown or luxe furs.

Praline followed Balmain when he left Lucien Lelong. And it was Pierre Balmain who gave her a new name. Balmain felt that a name like Jeannine was too “commonplace”—and after seeing her close his couture show in a pink-and-white gown, Balmain said that she was “as bittersweet as a Praline” and the name stuck.

She had an offbeat personality — always ready to play the clown. But she was also totally unpredictable. For example, she would sometimes just vanish a few hours before a show—forcing members of the Balmain team to take off all over the city in search of her. Once they found her at a railway station, another time at Orly airport—both times, she had her ticket in hand, all set to escape on a quick trip away from Paris…

Crazy unreliable, yes, but… she was definitely no dummy. She’d only flee the Balmain showroom AFTER the house’s couture dresses had been sewn to fit only her. Before that, she would never dream of missing a fitting,—because then Pierre Balmain could simply choose another model to replace her.

That volatility and unreliability meant that she and Pierre Balmain—although always very close—had quite a few loud arguments.

Praline was one of the few Paris showroom models who managed to attain true celebrity status in France.

There was a hit song written about Praline by Eddie Constantine and sung by Jean Sablon. And she also published a best-selling autobiography—“Praline: Mannequin de Paris”—at age 30!

Throughout, in spite of her modeling success at Balmain, she remained intent on becoming a movie star.

She was cast a few times in small roles, as a Parisian couture model in films — and then later she began acting in a few French films, under her real name Janine Marsay (her husband, Michel Marsay, was also an actor).

But she died in 1952, at age 31, when she was killed in a car accident.

Balmain was devasted when he heard the news. At her funeral mass at Paris’ enormous Church of Saint Agustin, her coffin was completely covered in pink roses and the crowd of onlookers was said to be enormous — the funeral was a media event, covered in all the Parisian magazines of the time.

BRONWEN PUGH (AKA LADY ASTOR)

Every member of the Balmain cabine—just like every model at every other couture house—was selected in order to fill a specific role. To best show his different designs, Pierre Balmain explained that he basically wanted to have two types of models in his cabine.

The first type was defined as someone who was “cheeky and impishly elegant.” That was a role that Praline was perfect for.

The other type of Balmain cabine model was a classically elegant mannequin — someone who could be seen as more as an aristocratic “woman of the world.” Bronwen Pugh could definitely play that role. She gave off a haughty regal air—setting herself apart by her nonchalance and a sort of “I’m really too good for this” attitude.

Bronwen was born in 1930 in London. She was the upper-middle-class daughter of a judge and when she was nine, she was sent away to be educated in a traditional Welsh language and culture school. When she finished with that, she had dreams of becoming an actress. She enrolled in the Central School of Speech and Drama — but after she was told she was too tall for film or stage (she was almost 6 feet), she studied to be a drama teacher.

And then, once she graduated, it was clear that she wasn’t all that interested in taking any school staff positions. Instead, she did some modeling work for London designers and ended up getting an announcing job on the BBC Television, replacing a popular host who was on pregnancy leave. After that BBC job ended, in 1956, she flew to Rome to do runway shows and then went up to Paris, where Balmain wanted to hire her as soon as he saw her.

But not everyone at Balmain agreed. Balmain’s mother, Françoise Balmain, and the house’s directrice, Ginette Spanier, were both strongly against hiring her — they saw her as too big and too strange looking. Spanier even rather meanly suggested that she looked like someone from the Adam’s Family.

But Balmain was convinced that she was perfect for his house and, in time, he managed to convince the others. He was convinced that she was a new Garbo and he pushed her to study the Swedish actress’ films and style. And Bronwen did her homework.

Besides her height, pale complexion, thick brown hair and bright green eyes—and that Garbo-esque aristocratic look—Browen stood out because of her very distinctive, powerful walk during the house’s presentations. The New York Herald Tribune’s fashion critic Eugenia Shepard humorously described Bronwen’s haughty presence during one show, noting that Bronwen dragged her Balmain fur coat behind her “as if she just killed it and was bringing it back home to her partner.”

In 1959, she was recovering from a painful break-up when she started seeing William Astor. Astor—who liked his friends to call him “Bill”—was more formally known as the 3rd Viscount Astor. He was 22 years older than her, had been married twice and had two kids.

When they got married a year later, the British press loved the story of the Paris couture model from Wales marrying a man old enough to be her father—and who, incidentally, was also one of the richest men in the world.

Because, yes, Bill, being an Astor, was immensely wealthy.

He was a Baron and a Conservative Party leader. He also had a whole lot of properties—including a substantial stake in the Astor family trust, which owned several blocks of central Manhattan. He also had homes in London, Scotland, Ireland and across the United States…. And, perhaps most famously, he had an enormous palatial estate on the Thames River, known as Cliveden…

Astor and Cliveden were key ingredients of the Profumo Scandal, which rocked Great Britain in the early Sixties. The Profumo Scandal combined Russian spies, beautiful models (Bronwen), rich Tory peers (Bill), government ministers and lots of sex.

It brought down a government, helped to change the course of modern British history and destroyed quite a few careers and lives—including Bill and Bronwen’s.

Today, we can see plenty of parallels between the Profumo scandal and the recent Jeffrey Epstein scandal. There were a lot of powerful men who behaved suspiciously (at best) and a lack of suitable answers due to a surprise suicide.

In the end, Viscount and Lady Astor inevitably came to be seen as just one more example of members of a corrupt and dishonest elite that had for too long gotten away preaching one thing to the lower classes while living in a completely different manner behind the walls of their estates.

The Profumo affair destroyed the Astors’ marriage and their position in London society. With the public seeing Bill as a seedy playboy and adulterer—or, at the very least, a fool—they were completely eliminated from London society. Viscount Astor fled London and died in the Bahamas in 1966, of “a broken heart.”

But, whatever might have been Viscount Astor’s relationship with Ward, there seems to have been no evidence ever given of Bronwen Pugh being guilty of anything but poor judgement.

After Astor’s death, Bronwen radically changed her life.

She had long been attracted to the philosophy of the French Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and she converted to Catholicism. With her Astor inheritance, she moved to Surrey with her two daughters to set up a charismatic Christian community. She studied to become a psychotherapist, and was eventually appointed chairman of Religious Experience Research Centre in Oxford.

PRALINE'S HIT SONG

During this episode, Lynn Yaeger gave her own perfect spin to translated lyrics from an early 1950’s hit about one of Balmain’s stars: Praline. Paris has had many beautiful women (and men) working as in-house models—but there are few who ever managed to become as famous as Praline. And we can’t think of anyone who might have had a hit song written about them. This 1951 tune was written by Eddie Constantine and sung by Jean Sablon. The melody is introduced with an astounded spoken reaction — “wait, you don’t know who Praline is?” — and then breaks into the song that follows the Praline through one of her day as Balmain’s star model, beginning with her morning stroll down the Champs Elysées, following her through a hard day of shows , (while she always manages to keep looking perfectly put together), and finally, although she’s tired, she is persuaded to go out at night and ends up falling in love with the singer. That singer ends his tune by letting the listeners know that he is now the lucky guy who’s engaged to Praline. Et la vie est jolie!

Sur les Champs Elysées

Ses cheveux tout bouclés

Elle est fraîche et jolie,

C'est Praline regardez-la marcher

Elle a l'air de danser

Sur le coup de midi c'est Praline

Elle est toujours bien habillée

On dirait qu'elle est riche

Bien chapeautée, chaussée, gantée,

Elle a même un caniche

Car elle est mannequin

Du velours au satin

Elle pass' la journée, c'est Praline

Une robe du soir, le manteau rayé noir,

La robe de mariée, c'est Praline

Huit heur's tout' seule et fatiguée

Elle rentre chez elle

Demain il faut recommencer

Elle oublie qu'elle est belle

Sur les Champs Elysées

Des Messieurs distingués

Feraient bien des folies pour Praline

Ell' fait " non " gentiment

Ell' ne veut qu'un amant

" Et ce s'ra pour la vie " dit Praline

Le soir où je l'ai rencontrée

Ell' m'a fait un sourire et puis

On est aller danser

Après... j'peux pas vous l'dire

Depuis tout a changé nous sommes fiancés

Et la vie est jolie Ah! Praline

On va se marier c'est banal à pleurer

Mais c'est moi qui souris à Praline

A ma Praline

PRALINE

SUNG BY JEAN SABLON

℗ 1951 Parlophone / Warner Music France, a Warner Music Group Company

Composer: Bob Astor

Composer: Eddie Constantine

Writer: Francois Jacques

1 / 3

From her desk—set directly at the top of the impressive central staircase inside Balmain’s legendary address at 44 François Premier—Ginette Spanier oversaw the daily workings, logistics, selling, presentations and planning for the house of Balmain for over thirty years.

Group shots of early Balmain team members, including some of the in-house mannequins and others.

1 / 2

Pierre Balmain and Praline, during a special Balmain presentation in the late 1940s.

Photo Credits:

01 : Photo of Ginette Spanier, Balmain house model Marie-Thérèse, and Pierre Balmain from a CBS interview broadcast on American TV on January 8, 1960. Copyright Free. Source: Wikipedia Commons- 02 : Ginette Spanier with Pierre Balmain. ©Balmain

- 03 : Ginette Spanier (standing) directs some of the members of Balmain’s Cabine of in-house couture models. ©Balmain

- 04 : Ginette Spanier working inside the Cabine (backstage) with the house dressers, models and crew, during a Balmain haute-couture presentations. ©Balmain

- 05 : Ginette Spanier, backstage in the Balmain Cabine, directing the house’s team of models, dressers and assistants during one of Balmain’s daily haute-couture presentations. ©Balmain

- 06 : A photo from one of the Balmain daily haute-couture presentations. ©Balmain

- 07 : Ginette Spanier, in Balmain showroom, closely inspecting one of the house’s latest designs. ©Balmain

- 08 : Images, from the 1940s, of Praline, wearing Balmain gowns ©Balmain

- 09 : Images of Bronwen Pugh, wearing Balmain. ©Balmain

- 10 : Praline and Pierre Balmain. ©Balmain

Credits :

Balmain Creative Director: Olivier Rousteing- Audio: This Is Your Life, 09.02.1972: Courtesy of Ralph Edwards Productions, TIYL Productions & Fremantle

- Special Podcast Guest: Lynn Yaeger

- Episode Direction and Production: Seb Lascoux

- Balmain Historian: Julia Guillon

- Episode Coordination: Alya Nazaraly

- Research Assistance: Pénélope André and Yasmine Ban Abdallah

- Digital Coordination/Graphic Identity: Jeremy Mace

- Episode researched, written and presented by John Gilligan

To explore further:

Pierre Balmain: My Years and Seasons, (Doubleday, 1965)- Ginette Spanier: It Isn’t All Mink (Collins, 1959 and V&A Publishing, 2017)

- Ginette Spanier: And Now It’s Sables (R. Hale, 1970)

- Ginette Spanier: Long Road To Freedom (R. Hale, 1976)

- See acast.com/privacy for privacy and opt-out information.